4.27.2005

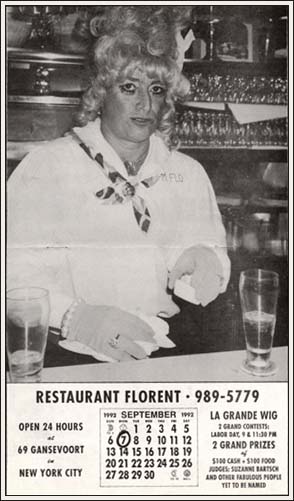

Snippy Seen-It-All Goofballs Serving Food 24/7.

When I found out that Florent was being reviewed by Frank Bruni in the New York Times, I exhibited the same befuddlement as the people to whom I told this fact.

"Florent? They're reviewing....Florent?"

Usually, such ballyhoo is reserved for the places attached to a chef du jour: Tourondel, Takayama, Palaccio, Dufresne, Keller. You expect to see the names of the modern restaurateurs: Vongerichten, Boulud, McNally or Chodorow. New York is a town whose restaurant politics rival the drama at the state legislative level. Here, chefs are literally taste makers and not just cooking performers like the dolts on the Food Network.

Competing fine dining establishments compare stars like generals in a war. Unlike most restaurants put through the Times ringer, however, Florent's fate does not rest within the Dining In, Dining Out section.

For Florent to get ink at this point in his career is a feat as indomitable as the man himself.

A Fanciful Bistro, but Not Too Fancy

by Frank Bruni

About a year and a half ago, in a fit of unwarranted panic, Florent Morellet determined that he could no longer close his restaurant, Florent, between 5 and 9 a.m. on weekdays and had to return it to its original 24-hour schedule.

The trigger for that decision said everything about the evolution of Manhattan's once gritty meatpacking district. Mr. Morellet had heard a dread prophecy: that Starbucks, which already operated one store about six blocks away, might open another within a few hundred feet. And he couldn't abide the thought of too many more early risers going over to the dark side of skim caramel macchiatos.

To compete, he put green Florent logos on to-go cups.

"Always be positive and proactive," he explained during a recent telephone conversation, laughing a tinkling laugh.

An upbeat, mischievous spirit is much of what has propelled Florent, with its pink neon sign and red vinyl banquette, its goofball servers and eclectic clientele, through nearly two decades since it served its first steak frites in August 1985.

But despite its minor adjustment for a Starbucks that didn't come, it has less often bent to shifting trends and times than bucked them, staying largely the same while all around it changed, while the muscle of the Mineshaft gave way to the Manolos of Spice Market and risqué was usurped by chardonnay.

The secret to Florent's enduring success is its integrity, which has now brought it full circle. After years when it was a naughty urban adventure and years when it felt like a tired cliché, it is once again what it was always meant to be: a simultaneously sensible and kooky bistro with onion soup and escargots, boudin noir and burgers, crème caramel and chocolate mousse, at reasonable prices that underscore its welcoming way. Florent is open to all and it is open all the time.

I went at 9:45 p.m. on a recent Friday and found it jammed, but Darinka, who began working there 19 years ago and wears her hair in a retro beehive, promised me a table in five minutes. I arched an eyebrow.

"Would I lie to you?" she said coquettishly.

My friends and I had to wait only four minutes, which whizzed by as we surveyed the other diners: a lone fortysomething man reading The Economist at the Formica counter; a gaggle of thirtysomething Italian speakers at a round Formica table; smatterings of twentysomethings with bulky black eyewear, the training wheels of hipness.

Our food came almost instantly, and almost all of it was evidence that Florent was not coasting on mere nostalgia. The grilled tuna in a generous Niçoise salad was rare, tender and nestled beside a sliced egg that had not been boiled too long. A duck pâté delivered the creamy richness we wanted. Roasted chicken was crispy and moist. Many fancy restaurants bungle that.

I went at 2:30 a.m. on a Saturday and chose a juicy, plump cheeseburger on an English muffin as a sponge for too much alcohol earlier on. It was gone in a flash, as was a friend's equally juicy, plump chicken breast sandwich. But we lingered in a happy crowd of young revelers, straight and gay, who canoodled in corners and tried to make the night last just a little longer.

And I went for weekend brunch, walking past the hordes clamoring for admission to Pastis. Florent had open tables.

There were tourists with maps but also downtown parents with strollers, and there was a younger waitress who might someday be Darinka. She didn't have the hair, but she had the arch attitude.

"Give me one second," I said as two friends and I glanced at menus.

"One second," she said. "Another second."

We ate an omelet, sausage, French toast and eggs Benedict, the bland, sticky hollandaise proving to be the lone false note. There were quick, regular refills on the coffee, which was seasoned with cinnamon, a trick I hadn't employed or experienced since college. It made me smile.

Florent has never chased sophistication or, for that matter, excellence. The wines in its limited selection are listed by region or grape, but not producer and year. Its desserts are uninventive and unexceptional.

Its shoestring fries, which are central to its mission, sometimes sag a bit. Its crab cakes, which are not, look and taste as much like falafel as anything born of the sea. Sane people don't go to Florent for them.

They go for the basics, expecting satisfaction, not bliss. They go for its frumpy individualism, which once made it a darling of the downtown art crowd and which it wears in too blunt and low-key a fashion to lapse into shtick.

And they go because Florent is more than a restaurant. It's a piece of social history and an ode to Mr. Morellet, 51, a transplanted Parisian so famous in some circles that his last name is as unnecessary (and unknown) as Bjork's. She, of course, has come to his restaurant many times.

He put it in the meatpacking district because he romped in the gay bars in the area at the time. He took over a Greek luncheonette, with its shiny aluminum and careless lighting, and he never changed the layout or cosmetics all that much.

But he sprinkled it with his brimming wit and his quieter sentimentality. Among the unmarked maps of unidentified cities on the walls are three imaginary ones, which he drew, and one map of a country, Liechtenstein. It hangs above the spot where the artist Roy Lichtenstein, who died in 1997, used to sit.

On the menu board are ever-changing lists, such as a spring to-do list ("abolish Congress") and ways to survive 2005 ("vacation outside the U.S."). The unexplained numbers on the bottom track Mr. Morellet's T-cell count, which he said has been improving with new medications. He tested positive for H.I.V. in 1987.

His restaurant, like him, is a survivor, and it has adapted, but not so very much. That Niçoise has been supplemented with a seared tuna salad with wasabi aioli. That roast chicken is now free-range. The baguette that used to cradle that chicken sandwich has been replaced by seven-grain bread.

And then, of course, there are those cups with green logos. Just don't expect Florent to be filling them with frappuccinos anytime soon.

link * Miss Marisol posted at 3:21 AM *

posted by Miss Marisol @ 3:21 AM

|